Evolution/Revolution

In all my screenwriting courses and workshops around the world, I’ve read thousands and thousands of screenplays. Exactly how many, I really don’t know. I lost count many years ago. But no matter what country or city I happen to be in, I am usually asked the same question over and over again: what do I find to be the biggest and most common problem of screenwriters? Well, there are many of course: lack of the main character’s dramatic need; structural weakness in the second act, lack of a strong ending, etc, etc.? But the main problem I find is usually the same: most screenwriters tell their story in dialogue, in words, constantly explaining the thoughts, feelings and emotions of the characters.

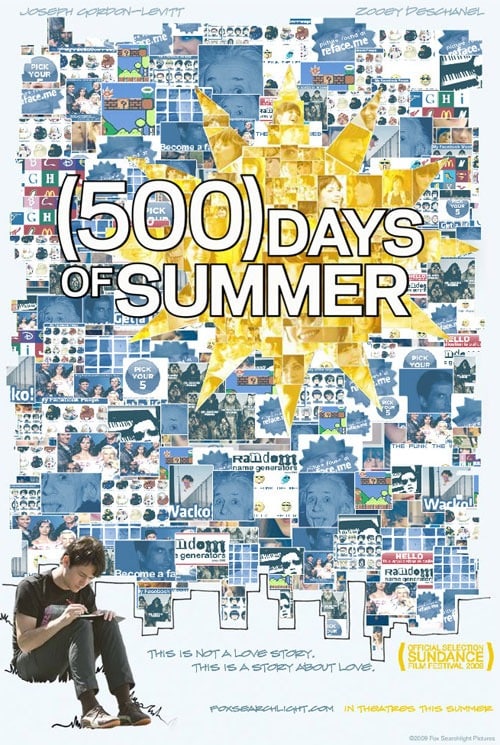

In and by itself, that’s not necessarily a “fault.” It really depends on what kind of story you’re writing. If it’s a romantic comedy like (500) Days of Summer, the action moves forward by dialogue, no matter how non-linear the story happens to be. In the case of Summer, the strong emotional through-line of the relationship anchors the story. The story of the relationship is a linear story-line, and it is simply told in a non-linear way. It works. Beautifully.

Today, changes are going on; stylistic changes. More and more the screenwriter is using many of the tools of the novelist: point of view, memory, subjective elements, voice-over narration, flashbacks etc. It has changed the look of the contemporary screenplay.

I was reminded of this a short time ago when I ran into an acquaintance I hadn’t seen for a while. We went to the nearby Coffee Bean and over a flavorful ice-blended started catching up with our lives. He’d been writing several TV shows, his kids had grown, and he had a feature idea he was playing around with. He asked what I’ve been up to and I told him I’ve been traveling almost non-stop for the past two years, giving seminars and workshops on screenwriting.

He asked me if I had “noticed” any differences in screenwriting from country to country. I told him no, that international screenwriting had evolved to a point where it was just “screenwriting.” I’m finding that no matter where I am in the world, whether in Brazil, Cairo, Madrid, Manila, Mexico City, Bombay, Singapore, or Vienna, independent of what language is spoken, a screenplay is still a “story told with pictures.” For me, as I’m constantly stating, it’s the screenwriter’s job to remain true to the culture they’re a part of. So many writers around the world want to write “a Hollywood movie” instead of focusing on their own cultural heritage and issues.

What I have noticed, I told my friend, is that the screenplays are becoming more visual, more fragmentary, in terms of scope, form and execution. And, I shared an experience I had when I spent several weeks working with the writer and director as a script consultant on a film (to be released in 2010 by Fox) titled My Name is Khan. It didn’t matter that this was an Indian film, or that it was written by one of my students. Khan is really a story that impacts our humanity. It transcends language, country and culture. Since the story-line was about a journey, with moments of flashbacks and memories, I suggested they use more voice-over narration so we could gain more of an insight into the character. In that way, there didn’t have to be so much explanation. That meant that we had to re-structure most of the story-line, especially in the beginning and I feel, gave it a stronger emotional impact. (When it’s released, we’ll see how accurate I am.)

I suggested using the voice-over narration because there’s a simple rule in screenwriting – either the character drives the action, or the action drives the character. In this case, the character drives the action (same as (500) Days of Summer, Shawshank Redemption or Juno,). An example of action driving the character would be Little Miss Sunshine, Slumdog Millionaire or The Lookout.

From my vantage point, the craft of screenwriting today has evolved, and is continuously evolving into what I call a “revolutionary form.” Look at: Atonement, Vantage Point, Slumdog Millionaire or Inglorious Basterds. Almost every film being released today uses elements of voice-over, sub-titles, flash-present, interviews, or other elements of a multi-media presentation. To me, it is the mark of a new style of screenwriting.

Why is this happening? Well, I have a “theory” about that. I believe that this “new” style of screenwriting is evolving through the influence of technology. And it’s creating a “revolution” in the way we’re writing our screenplays.

Utilizing an analogy with texting, we’re using less words and more pictures to show/explain things. R u wi me? Today, we think in pictures, not words. As I always say, Film is Behavior. Because of this advance in technology, the world has become a smaller place and more information from anywhere in the world can be retrieved almost instantaneously.

So, you may be wondering: What is this Evolution/Revolution that’s going on?

I believe – and it’s my own personal theory, by the way, which is validated by many scientists- that this rise of technology is imprinting itself as an evolutionary form of behavior. We see, we don’t explain in film, how a character acts or reacts to a specific incident or event. Their behaviors illuminate their character, reflect their value systems and morality, and reveal who they are more by their actions than their words. Because of this evolutionary process, things are changing; we’re seeing the same things, we’re just seeing them differently.

Here’s how I look at it: the rise of digital technology. BD (Before Digital) we had Analog Technology – meaning that all signals, or bytes of information, are singular and individual: sound is read as sound, music is read as music, picture is read as picture. And if you were building a “composite” movie track you would be pile each track layer upon layer – a layer of music, a layer of effects, a layer of dialogue, just like laying down sheets of pasta when you’re making lasagna.

But digital moved us to a different level. Digital technology is different: all signals, or bites of information, are read as being the same – they are read, or interpreted as one component. So, all bytes of sound, picture and music are read as one unit of information. Like making soup, you take all the ingredients (the analog), then put them in a pot, and when they’re all blended together… you have soup (digital). You can’t separate the ingredients, because they’re now one!

We can do things technically in film today that we couldn’t do ten years ago. And more importantly, at least from my perspective, we can include bits and pieces of a character’s memory into the story-line so it becomes an integral part of the action. Look at The Bourne Supremacy and The Bourne Ultimatum. We didn’t have that technology 20 years ago to incorporate a character’s past or memory fragments into a character’s behavior. Today, with digital technology, we’re able to utilize a character’s memory as part of their character development and incorporate it into the story-line.

Here’s an example of what I’m talking about. Look at a classic film like Casablanca. There’s a scene in the first act where the German, Major Strasser, invites Rick to join them at their table for a drink. He begins to ask Rick questions: What’s your “profession,” he asks? “Drunkard,” Rick replies. Already you hear his rebellious nature. Irritated, the German pulls out his little black book and begins to tell us all about Rick. It’s all expository dialogue designed to give us information about who Rick is, his past, where he came from, and this exposition reveals why he might be a potential danger to the Nazis in Casablanca. It’s all words, talking heads. Yes, it still works, but it’s the old, classic way of giving us information that’s necessary to move the story forward. You’ll see this style in The Hustler, The Apartment, and many other films.

But, here’s the new way of giving us the same character exposition for Rick. At the beginning of The Bourne Ultimatum, Jason Bourne is riding on a train and is reading a newspaper. He sees his name in the paper and as he reads the story, we cut into bits and pieces of Bourne’s visual memories. These visual fragments serve an expository function the same way that Major Strasser’s reading about Rick’s character in Casablanca does. If we’ve never seen any of the Bourne series we learn things about him that were in the previous two films. And, it’s done in a little more than a minute. All pictures, no words. In Casablanca, the information is simply inserted into the story-line, (like the love story told in flashback between Rick and Ilsa), whereas in the Bourne films, these bits and pieces of memory are integrated into the story-line.

This is what I’m talking about in terms of the Evolution/Revolution of the modern screenplay. Take a look and check it out.

Comments are closed.