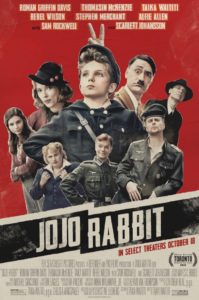

JoJo Rabbit

Based on the Book “Caging Skies” by Christine Leunens

Storyline by Shari Goodhartz:

Ten-year-old, aspiring Hitler youth JoJo enjoys an imaginary friendship with Adolf himself while being forced to reckon with cognitive dissonance on learning that his delightfully playful mother is hiding a 17-year-old Jewish girl in their house.

Film & Paradigm Analysis by Shari Goodhartz:

Act I sets up aspiring Hitler Youth JOJO (10) enjoying an imaginary friendship with a wacky version of ADOLF. JoJo attends CAPTAIN KLENZENDORF’s weekend training camp, where he’s bullied for being unwilling to kill a bunny. Adolf convinces JoJo to shame the other boys by throwing a live hand-grenade, which bounces off a tree and injures JoJo. His mother ROSIE is revealed to be incredibly playful and loving.

With his face, arm and leg injured, Plot Point I finds JoJo discovering that a Jewish girl named ELSA (17) is hiding in their house. They verbally spar and she easily takes his camp knife.

At the top of Act II, Rosie secretly visits Elsa. They discuss JoJo, who confirms that his mother is hiding a Jew but won’t confront her. Instead, he visits Captain Klenzendorf to learn more about the demon-like nature of Jews.

Klenzendorf demurs, but says someone ought to write a book about it. JoJo decides to interview Elsa and write such a book. To JoJo’s great displeasure, Rosie reports that the Allies are winning the war, then good-naturedly cheers him up.

At the Midpoint, JoJo poses as Elsa’s fiancé in a break-up letter, intending to hurt her. She is saddened, but not for the reasons he thinks. He quickly writes a second letter undoing the first.

In the second half of Act II, Rosie reiterates that the Reich is dying. JoJo spends more time with Elsa while composing his fancifully nasty exposé on Jews with illustrations. Adolf disapproves of JoJo spending so much time with Elsa, who tells JoJo he’s not a Nazi. JoJo realizes he’s in love. When Gestapo agents visit the house, Elsa pretends to be JoJo’s devoted-Nazi sister and gets away with the ruse because the SS are charmed by JoJo’s book. Klenzendorf also provides some sly help.

Plot Point II finds JoJo collecting metal door-to-door for the war effort. He discovers Rosie hanging in the street with other subversives.

Elsa tries to comfort JoJo in Act III, revealing that she suspected both Rosie and JoJo’s MIA father work for the resistance. JoJo fears his mother hated him for being a Nazi. JoJo learns how Rosie saved Elsa, and that Hitler killed himself. After saving JoJo’s life, Klenzendorf is killed by a Russian soldier. Elsa admits her fiancé died last year of TB and they decide to love each other as siblings. At the Climax, JoJo power-kicks Adolf out of his bedroom window.

The story is Resolved when JoJo takes Elsa outside by recalling a ruse his mother used earlier on him. They dance in the street as American soldiers drive past.

I didn’t understand how Annie Hall was put together. I had to approach my analysis from a different perspective. I wondered if you could structure a story around the growth and change of a character? Alvy is a person who refuses to change, whereas Annie Hall is a person who changes and grows constantly. Can a screenplay told mostly in flashback be structured around the dramatic need of the character?

I didn’t understand how Annie Hall was put together. I had to approach my analysis from a different perspective. I wondered if you could structure a story around the growth and change of a character? Alvy is a person who refuses to change, whereas Annie Hall is a person who changes and grows constantly. Can a screenplay told mostly in flashback be structured around the dramatic need of the character? The movie unfolds from Alvy’s point of view. In the dictionary, “point of view” is defined as “the way a person sees the world.” And Alvy certainly “sees” his world in a bizarre and unusual way.

The movie unfolds from Alvy’s point of view. In the dictionary, “point of view” is defined as “the way a person sees the world.” And Alvy certainly “sees” his world in a bizarre and unusual way. Near the end of Act II, almost at the end of their relationship, there’s a marvelous scene, among many, done in split scene, where Annie and Alvy are both seen in therapy sessions; Alvy lies on a couch, Annie sits in a chair. Both lament the fact their feelings have changed toward each other, but it’s how they see the same thing that brings the humor out. Both psychiatrists ask “do you have sex often?” and Alvy replies “Hardly ever. Maybe three times a week.” And Annie replies: “Constantly! I’d say three times a week.” It’s a perfect illustration of “The world is as you see it” as the ancient scriptures say.

Near the end of Act II, almost at the end of their relationship, there’s a marvelous scene, among many, done in split scene, where Annie and Alvy are both seen in therapy sessions; Alvy lies on a couch, Annie sits in a chair. Both lament the fact their feelings have changed toward each other, but it’s how they see the same thing that brings the humor out. Both psychiatrists ask “do you have sex often?” and Alvy replies “Hardly ever. Maybe three times a week.” And Annie replies: “Constantly! I’d say three times a week.” It’s a perfect illustration of “The world is as you see it” as the ancient scriptures say.

It took me several viewings to understand that one of Antonioni’s greatest achievements in illustrating characters is that they see themselves in each other. Visiting their dying friend in the hospital they ride in the elevator, and carefully avoid looking at each other. Two people, separate, but together, without emotional bonds of sympathy or encouragement. Their dying friend tells Giovanni and Lidia that being in the hospital has given him time to think and it’s only now that he understands that he is a person who “lacks the courage to get to the bottom of things.” In a way, he could be speaking for Giovanni as both sense they are seeing a reflection of their own lives.

It took me several viewings to understand that one of Antonioni’s greatest achievements in illustrating characters is that they see themselves in each other. Visiting their dying friend in the hospital they ride in the elevator, and carefully avoid looking at each other. Two people, separate, but together, without emotional bonds of sympathy or encouragement. Their dying friend tells Giovanni and Lidia that being in the hospital has given him time to think and it’s only now that he understands that he is a person who “lacks the courage to get to the bottom of things.” In a way, he could be speaking for Giovanni as both sense they are seeing a reflection of their own lives. Later, at an evening party given in honor of Giovanni by a wealthy industrialist, Lidia is tempted by a rich playboy, while Giovanni is tempted by Valentina (Monica Vitti), the daughter of their host. When it begins to rain, many of the partygoers seek a diversion by leaping into the pool. Giovanni and Valentina share some pleasant moments together, and like many strangers, share their most intimate thoughts. He tells her “I believe now that I’m no longer capable of writing. I know what to write but not how to write it.” Like many of Antonioni’s characters, Giovanni’s personal life is reflected in his inability to work; he is what he does. It’s not his ideas and convictions that have been lost, but the force, the energy, and the inner fire to create a work of art, which has been lost. Ideas are part of his make-up; they may change, evolve, come and go, but they are never lost. It’s in the physical act of producing his work that Giovanni has become powerless.

Later, at an evening party given in honor of Giovanni by a wealthy industrialist, Lidia is tempted by a rich playboy, while Giovanni is tempted by Valentina (Monica Vitti), the daughter of their host. When it begins to rain, many of the partygoers seek a diversion by leaping into the pool. Giovanni and Valentina share some pleasant moments together, and like many strangers, share their most intimate thoughts. He tells her “I believe now that I’m no longer capable of writing. I know what to write but not how to write it.” Like many of Antonioni’s characters, Giovanni’s personal life is reflected in his inability to work; he is what he does. It’s not his ideas and convictions that have been lost, but the force, the energy, and the inner fire to create a work of art, which has been lost. Ideas are part of his make-up; they may change, evolve, come and go, but they are never lost. It’s in the physical act of producing his work that Giovanni has become powerless. A lot of people did not like La Notte because they claimed “nothing really happens;” there is no plot, no action and it’s way too long. Some critics asserted the film is simply an “empty testament of modern life,” not even a “slice of life,” and they viewed Antonioni as a filmmaker who is too internal, focusing on what does not happen, rather than on what could happen. Whatever that means. Like Rashomon, everyone saw something different.

A lot of people did not like La Notte because they claimed “nothing really happens;” there is no plot, no action and it’s way too long. Some critics asserted the film is simply an “empty testament of modern life,” not even a “slice of life,” and they viewed Antonioni as a filmmaker who is too internal, focusing on what does not happen, rather than on what could happen. Whatever that means. Like Rashomon, everyone saw something different.

When I talk about Magnolia in my seminars and workshops, some people object and tell me it’s too long. They say it’s too melodramatic. They tell me it pushes the boundaries of reality. Yes, thank God. It’s the brilliance of Anderson’s vision, the intelligence of the emotional tapestry that he weaves into his fluid style of filmmaking that makes it so powerful.

When I talk about Magnolia in my seminars and workshops, some people object and tell me it’s too long. They say it’s too melodramatic. They tell me it pushes the boundaries of reality. Yes, thank God. It’s the brilliance of Anderson’s vision, the intelligence of the emotional tapestry that he weaves into his fluid style of filmmaking that makes it so powerful. The more I studied the film, the more I saw that it revolves around the dying Earl Partridge. On this, the very last day of his life, Earl wants Phil, his nurse, to find his son, Frank T.J. Mackey. Earl, as seen on the background credits on the always playing TV, is the owner/producer of the What Do Kid’s Know show, where Stanley is a key contestant. Linda is Earl’s wife. Jimmy Gator works for Earl, and, as we’ll learn later, Jimmy molested his daughter, Claudia.

The more I studied the film, the more I saw that it revolves around the dying Earl Partridge. On this, the very last day of his life, Earl wants Phil, his nurse, to find his son, Frank T.J. Mackey. Earl, as seen on the background credits on the always playing TV, is the owner/producer of the What Do Kid’s Know show, where Stanley is a key contestant. Linda is Earl’s wife. Jimmy Gator works for Earl, and, as we’ll learn later, Jimmy molested his daughter, Claudia. When Phil drops the liquid morphine into his mouth, it’s the end, but as it turns out, Earl’s death is really a new beginning because it’s the catalyst that brings everyone together. As the rain thunders down, we see the nine characters singing about their pain and guilt and lack of self-worth, knowing it’s just not going to stop “til you wise up.”Now that you’ve met me, would you object to never seeing me again?” Claudia asks Jim Kurring. Until they can accept themselves for who they are, until they can forgive themselves and accept their own sense of self-worth, until they can let somebody love them for who they are and let the past go, it’s not going to stop. Just “wise up.”

When Phil drops the liquid morphine into his mouth, it’s the end, but as it turns out, Earl’s death is really a new beginning because it’s the catalyst that brings everyone together. As the rain thunders down, we see the nine characters singing about their pain and guilt and lack of self-worth, knowing it’s just not going to stop “til you wise up.”Now that you’ve met me, would you object to never seeing me again?” Claudia asks Jim Kurring. Until they can accept themselves for who they are, until they can forgive themselves and accept their own sense of self-worth, until they can let somebody love them for who they are and let the past go, it’s not going to stop. Just “wise up.” The falling of the frogs is taken from the Bible, Exodus, Book 8, where the plague of frogs descends from the sky punishing the Pharaoh for betraying Moses and the Hebrews in the land of Egypt. As I began exploring the backgrounds of the scenes in the film, I kept seeing references to “8:2” in the audience at the TV show, or on outdoor signs on Magnolia Blvd. in the San Fernando Valley.

The falling of the frogs is taken from the Bible, Exodus, Book 8, where the plague of frogs descends from the sky punishing the Pharaoh for betraying Moses and the Hebrews in the land of Egypt. As I began exploring the backgrounds of the scenes in the film, I kept seeing references to “8:2” in the audience at the TV show, or on outdoor signs on Magnolia Blvd. in the San Fernando Valley.

It was a huge topic, to be sure, and I tried to answer it by saying that Pulp Fiction seemed to spark a new awareness in the filmgoer’s consciousness. Yes, I added, we were riding a wave of change, and while technology would definitely affect the movies, the real “revolution” was going to manifest itself more in terms of form than content. That is, what you show and how you show it. Pulp Fiction is definitely a part of that.

It was a huge topic, to be sure, and I tried to answer it by saying that Pulp Fiction seemed to spark a new awareness in the filmgoer’s consciousness. Yes, I added, we were riding a wave of change, and while technology would definitely affect the movies, the real “revolution” was going to manifest itself more in terms of form than content. That is, what you show and how you show it. Pulp Fiction is definitely a part of that. I remembered Henry James’ literary question: “What is character but the determination of incident? And, what is incident but the illumination of character?” If this key incident is the hub of the story, as I now understood it, then all things, whether actions, reactions, thoughts, memories, or flashbacks, are tethered to this one incident.

I remembered Henry James’ literary question: “What is character but the determination of incident? And, what is incident but the illumination of character?” If this key incident is the hub of the story, as I now understood it, then all things, whether actions, reactions, thoughts, memories, or flashbacks, are tethered to this one incident.

At this point, we still don’t know what’s going on. Because the filmmakers have completely grabbed our attention, it’s precisely at this moment that we need information; we need to know what the story is about, who’s the main character, and what’s the dramatic situation. In dramatic terms, exposition is defined as the necessary information needed to move the story forward. Trinity tells Neo that he’s in danger because he’s expressed the desire to know who or what the Matrix is. She stresses “the truth is out there, Neo and it’s looking for you and will find you, if you want it to.” Then she’s gone.

At this point, we still don’t know what’s going on. Because the filmmakers have completely grabbed our attention, it’s precisely at this moment that we need information; we need to know what the story is about, who’s the main character, and what’s the dramatic situation. In dramatic terms, exposition is defined as the necessary information needed to move the story forward. Trinity tells Neo that he’s in danger because he’s expressed the desire to know who or what the Matrix is. She stresses “the truth is out there, Neo and it’s looking for you and will find you, if you want it to.” Then she’s gone. As a side note, one of the things I found interesting was the names used in The Matrix. When I started exploring their origin, I found they’re derived from ancient history and mythology. They reflect an metaphoric significance. The name of Morpheus’s ship, for example, the Nebuchadnezzar, is named after the Babylonian king who lived in the Fifth Century, BC. Heralded as the greatest king of the Babylonian Dynasty, he’s credited with tearing down, then re-building the ancient temples, so he is both a destroyer and re-builder. The name fits the ship’s destiny for it houses the rebel force bent upon destroying and rebuilding the Matrix. The same with Morpheus; in Greek mythology, he is the God of Sleep, building and weaving the fabric of our dreams in the deep sleep state. Neo, of course, means “new,” and the religious implications of Trinity are obvious.

As a side note, one of the things I found interesting was the names used in The Matrix. When I started exploring their origin, I found they’re derived from ancient history and mythology. They reflect an metaphoric significance. The name of Morpheus’s ship, for example, the Nebuchadnezzar, is named after the Babylonian king who lived in the Fifth Century, BC. Heralded as the greatest king of the Babylonian Dynasty, he’s credited with tearing down, then re-building the ancient temples, so he is both a destroyer and re-builder. The name fits the ship’s destiny for it houses the rebel force bent upon destroying and rebuilding the Matrix. The same with Morpheus; in Greek mythology, he is the God of Sleep, building and weaving the fabric of our dreams in the deep sleep state. Neo, of course, means “new,” and the religious implications of Trinity are obvious. Neo’s decision to rescue Morpheus is Plot Point II; that incident, episode or event that hooks into the action and spins it around into another direction, in this case, Act III. Remember at Plot Point I, in their first encounter, Morpheus asks Neo if he believes in fate, and Neo replies, no; “Because I don’t like the idea that I’m not in control of my life.” At this point, it really doesn’t matter whether he believes it or not; it’s his fate, his destiny.

Neo’s decision to rescue Morpheus is Plot Point II; that incident, episode or event that hooks into the action and spins it around into another direction, in this case, Act III. Remember at Plot Point I, in their first encounter, Morpheus asks Neo if he believes in fate, and Neo replies, no; “Because I don’t like the idea that I’m not in control of my life.” At this point, it really doesn’t matter whether he believes it or not; it’s his fate, his destiny.

It didn’t take long for me to see that the character of Ethan Edwards is different than most of the other parts John Wayne plays, whether in Stagecoach, Red River, She Wore a Yellow Ribbon or Fort Apache. In The Searchers, Ethan Edwards is a person who doesn’t belong anywhere, the outsider, a man doomed to “wander on the wind.” As the story unfolds, the thin line between obsession and revenge, the opposite poles of “civilization” and “wilderness” become totally blurred.

It didn’t take long for me to see that the character of Ethan Edwards is different than most of the other parts John Wayne plays, whether in Stagecoach, Red River, She Wore a Yellow Ribbon or Fort Apache. In The Searchers, Ethan Edwards is a person who doesn’t belong anywhere, the outsider, a man doomed to “wander on the wind.” As the story unfolds, the thin line between obsession and revenge, the opposite poles of “civilization” and “wilderness” become totally blurred.

The first thing I noticed is that John Wayne’s character doesn’t change. There is no transformation in his character; he’s exactly the same at the end of the movie as he was at the beginning. Wayne’s image, as a man of action, is heroic precisely because he does not change; he refuses to give up, bend or alter his ways until his mission is accomplished; to find and rescue the kidnapped girl. And when he does find her, we don’t know whether he’s going to kill, or embrace her. Finally, in a dramatic scene, he relents and embraces her. At the end, when the family enters the house to celebrate their return, Wayne remains outside the doorway, a desolate, homeless drifter doomed to wander “between the winds.”

The first thing I noticed is that John Wayne’s character doesn’t change. There is no transformation in his character; he’s exactly the same at the end of the movie as he was at the beginning. Wayne’s image, as a man of action, is heroic precisely because he does not change; he refuses to give up, bend or alter his ways until his mission is accomplished; to find and rescue the kidnapped girl. And when he does find her, we don’t know whether he’s going to kill, or embrace her. Finally, in a dramatic scene, he relents and embraces her. At the end, when the family enters the house to celebrate their return, Wayne remains outside the doorway, a desolate, homeless drifter doomed to wander “between the winds.”