Ted Tally – On Adaptation

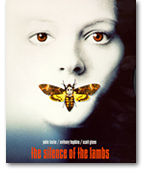

The Silence of the Lambs

As you know, the art of adaptation is a very special craft, some even call it a “gift,” and there are many ways to approach adapting a novel, or magazine article, or newspaper story, or personal experience, into an effective and meaningful screenplay.

I first became aware of Ted Tally’s work when I was called in as a special consultant for the movie, White Palace. Ted had written the first draft and then Alvin Sargent, the noted writer of Ordinary People, Julia, Straight Time, and a slew of others, was brought in for the rewrite.

Several years later, when I was writing my book Four Screenplays, one of the four films I analyzed to show the relationship between the movie and the screenplay was Ted Tally’s adaptation of Silence of the Lambs, and I had been so impressed with the quality of his work, that I wanted to find out how he goes about adapting a novel into a screenplay.

As far as I’m concerned, Ted Tally is one of the best at his craft. What he has to say about the art of adaptation is simple, yet eloquent, practical, yet creative.

Ted Tally won the Academy Award for the Best Adapted Screenplay of The Silence of the Lambs. He also adapted The Juror and Before and After.

If you haven’t seen The Silence of the Lambs, or if you saw it a long time ago, I would recommend that you see it again and watch the mastery of Ted Tally’s adaptation.

Ted Tally

“As far as I’m concerned, adapting a novel into a screenplay is just like writing an original screenplay. The two forms are as different as an apple and orange. Though both may be fruits, and both grow on trees, they are totally different in taste, color, and texture.

“Whenever I approach a new adaptation, I approach it as if I were writing an original screenplay. The first thing I do is read the novel just as a general reader, looking for the story, interesting characters, and a narrative flow of action. Then, I put it aside, and think about it for several days, about the characters, about the events, and how I can take those events and translate them into pictures.

“I find that most novels take place inside the character’s head; we see what he or she sees, listen to his or her thoughts, see the character from other character’s points of view, or simply follow an individual line of action that will intersect with the main characters later in the story.

“After I’ve sorted out the action, I go back and re-read the book from beginning to end. When I finish the book this time, I put it away and start writing down the scenes I remember the most. The scenes that stick out in my mind. I’ll usually remember about six or seven scenes, sometimes more, sometimes less. I’ll write down what I remember about the scene and possibly why I remember the scenes as being so vivid. I mean, what was it that attracted me to the scene within the context of the story?

“The first thing I have to do in any adaptation is a lot of reading and a massive amount of editing. The Silence of the Lambs, for example, was a 350-page novel and I had to reduce it into a 120-page screenplay, almost a third of the novel. At that point, I’m ready to begin working on the adaptation.

“The first thing I have to do in any adaptation is a lot of reading and a massive amount of editing. The Silence of the Lambs, for example, was a 350-page novel and I had to reduce it into a 120-page screenplay, almost a third of the novel. At that point, I’m ready to begin working on the adaptation.

“The first thing I do is break down the book scene by scene. That’s my method of working, the way I approach a screenplay adaptation. When I have all that broken down, I’ll try to establish and define the line of events; this event happens, then this event, then this and this happens, all the time trying to keep the integrity of the novel, or source material.

“What’s important for me is finding what sticks out in my mind. That’s when I’ll put those scenes down on cards, one by one, just getting the storyline down, concentrating on the needs of the adaptation.

“Adapting The Silence of the Lambs, for example, I knew this had to be Clarice Starling’s (Jodie Foster’s) story. Even though the book goes inside Hannibal Lecter’s mind, inside Crawford’s (Scott Glenn’s) mind, inside Jame Gumb’s mind, the book basically follows the character of Clarice.

“So, this had to be Clarice’s movie. Anything she’s not in, any scene that may be extraneous to furthering Clarice’s story, had to be cut, if possible. If it’s not cut, then it has to be kept to an absolute minimum. This story is her journey. Approaching it this way meant automatically reducing the book.

“One of the risks I had to take in Silence of the Lambs, for example, was the fact that we would not get to know very much about Jame Gumb; we wouldn’t have any background on him. He’s a mysterious figure to her. So, we have to see that through her eyes. If she finds out more about him, then we find out more about him. When she has to guess, we have to guess, too. But keeping a determined focus on Clarice meant losing a lot of wonderful things that were in the book. Jack Crawford’s dying wife, for example. I bitterly tried to hang on to that in the first couple of drafts, but by the third draft I realized it wouldn’t work; so, it had to go. I had to be ruthless in terms of what I kept and what I didn’t keep. Some things I managed to hold on to until the third and fourth drafts.

“For example, there was a sequence in the book where Clarice gets in trouble. She has a confrontation with Senator Martin, the mother of the kidnapped girl (played by Diane Baker). It’s a very strong scene and I wanted to hang on to it, but Jonathan Demme, (the director), simply said, ‘We don’t have time for this confrontation. The dramatic focus has to be on Clarice and Hannibal Lecter, then on Lecter’s escape.’ And he was right. It was a matter of paring down the action and shifting the scene order. Adaptation forces you to think in a logical way about telling the story.

“That’s means there was an enormous amount of material I have to leave out. When you’re reducing a book that dramatically, the author’s arrangement of the story does not necessarily hold up anymore. You may have to shift several scenes in order to follow the main storyline. And that means, in most cases, that I have to restructure the novel. Sometimes I even have to introduce new characters who were not even in the novel.

“That’s means there was an enormous amount of material I have to leave out. When you’re reducing a book that dramatically, the author’s arrangement of the story does not necessarily hold up anymore. You may have to shift several scenes in order to follow the main storyline. And that means, in most cases, that I have to restructure the novel. Sometimes I even have to introduce new characters who were not even in the novel.

“I always remember I’m adapting the source material; I’m not just transcribing the book into a movie. If I did that I’d end up with the novel in pictures. It wouldn’t be a movie, it would only be filmed rendition of the novel.

“I don’t work that way. I look at any adaptation, as mentioned, as an original screenplay. If the novel starts with character scenes, like The Juror, I have to find a way to grab the viewer’s attention immediately. So, in some cases, I may take a scene from the middle of the book and use it open the screenplay. The first few minutes of a movie are so important, I feel I have to grab the viewer’s attention.

“The last thing I’m concerned with is invention for its own sake. As the saying goes, ‘If it ain’t broke, don’t fix it.’ But because you’re deliberately breaking the book apart in order to make it into a screenplay, you’re going to have to invent new scenes. It might be inventing a way to meld two or three scenes from the novel into one scene in the screenplay. And that means you’re going to have to invent transitions to keep the action moving forward. And then you’re going to have to invent dialogue for those transitions because you’ve lost so much information it’s probably confusing.

“You can’t be a slave to the book. This has to be your source material, your screenplay. You want it in your head but you don’t want it oppressing you. After a while, you reference your own story outline more than you do the novel. And once you complete the first draft, you virtually have no reference to the published novel at all. It becomes about itself only. It starts to develop its own logic and it’s own meaning in writing.”

Comments are closed.